“My mother never talked about it,” Ed Penner remembers. “She didn’t want to pass on the terror that [her family] had endured in Russia at the hands of the KGB and the communists.”

Yet the past weighed on his mother: memories of her father arrested for being a kulak (rich farmer), her mother starving to death, a brother tortured to death by the KGB. Penner sensed his mother’s anguish, and it fostered his own “spirit of anger” toward the Russian people.

The modern descendants of Russian Mennonites have much to be angry about, even as the crimes themselves recede into the past. The legacy of Stalin and the Bolsheviks remains in stunted family trees and stolen inheritances, and adds poignance to post-war missions to Ukraine and Russia.

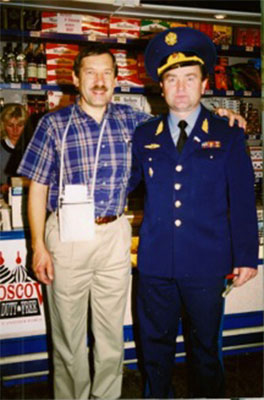

By 1995, married and with a career in dentistry, Penner seemed to have taken full advantage of the life his parents had bought for him by fleeing to Canada. Then, Bibles International representative Garth Hunt invited Penner to join a team of 70 medical professionals travelling to post-Soviet Moscow to provide medical assistance, and distribute 14,000 military-issue Bibles. The initiative was undertaken at the request of Russian General Nikolai Stolyarov, who, in Penner’s words, realized “that in order to rehab his PTSD soldiers in the military [mostly Afghanistan veterans], he needed a spiritual revival.”

Penner was intrigued by the opportunity, and, after serious soul searching, agreed to take part. He wasn’t prepared for the poor level of dental hygiene (“The dentistry was worse than Third World”) – nor the numerous KGB and army veterans who lined up for his services. “In the West, we got told that the Russians, they get free glasses, they get free hearing aids, they get free medical treatments – well, that was a big lie,” he says. “Military people, some of them were decorated officers – they had no insulin, penicillin was in short supply. The treatment for diabetes was very often just the removal of gangrenous limbs.”

Sometimes, Penner remembers, he would treat military officers with four or five abscesses. He asked the men, “How long have you had [abscesses]?” They replied, “As long as I can remember.” “What have you done about the pain?” “Vodka!”

One day, Penner got a call from Stolyarov himself asking if the dentist would work on his wife’s teeth. Penner remembers shaking as he conducted the procedures. This woman was married to a top KGB general: the same secret police whose authority bumped her to the front of the line outside Penner’s clinic had murdered thousands of Ukrainians including Penner’s own uncle. He was tempted to refuse to operate, but he felt an odd sympathy as well.

“I recognized too that these are just people who were basically betrayed in faith by godless Communism,” he says. “If you lay down your sword and you make a plowshare out of it, it is possible to forgive.”

The younger Russians who translated for Penner and his coworkers also helped him see his anger as part of the past instead of the present. “I loved the young people who worked with us,” he says, “and Major General Stolyarov was not a stooge. I believe his spiritual experience was vital and it was real.”

“There is the power of the gospel. To me, it was satisfying to see that it had a power that 70 years of godlessness could not squash,” says Penner. “To me, it was kind of vicarious evangelism. I didn’t pretend that just giving out a military Bible would change the heart of people, but the love we showed through our interpreters and our genuine help medically, I think that did make considerable impact.”

Penner says his heart is now settled. He remembers the tragedies within his family, but he no longer holds the Russian people accountable. He has made his plowshare.

—Paul Esau wrote this story as communications intern with CCMBC and MB Herald.