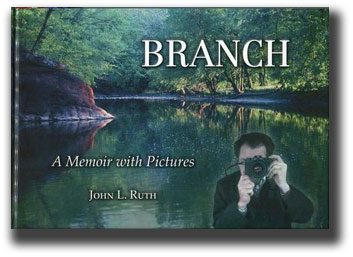

Branch: a memoir with pictures

Branch: a memoir with pictures

John L. Ruth

TourMagination & Mennonite Historians of Eastern Pennsylvania

“The story is an inner rainbow, a weaving of words and imagination and visualization,…a marriage of the head and heart,” writes Elaine M. Ward in The Art of Storytelling. Stories can “heal, educate, inspire, motivate, transform, make meaning, entertain and build relationships.”

Anabaptist-Mennonite historian, minister, writer, educator, photographer and world traveller John Landis Ruth reflects this in his book, Branch: A Memoir with Pictures. Not simply a run-of-the-mill memoir of introspective text interspersed with relevant pictures, Branch invites the viewer “to muse, not just glance.”

A 432-page coffee-table book, Branch is equally divided between a textual and visual format: full-page photo on one side, narrative on the opposite page. Some photos are those his parents took, but most are Ruth’s own – some black and white, some colour.

Branch reads as though Ruth sits beside the reader, showing a picture, then bringing texture and vibrancy. The image lives in the reader’s imagination as Ruth weaves his words and stories around it. And such words they are: “persiflage,” “anomie,” “eponymous” and “hegira,” to name a few. (I actually looked them up in the dictionary; professor Ruth is probably smiling.)

Ruth ranges through his 83 years with candour, honesty, humour and sensitivity, beginning with the foundational years of childhood and youth on the Eastern Pennsylvania farmland of his ancestors, close to Perkiomen Creek, commonly known as “the branch.” He finds his wife, Roma Jacobs, who becomes a sought-after Fraktur artist. They begin a family. Opportunities lead him to become a dedicated and passionate minister, conference leader, scholar, educator, researcher, writer, historian, photographer, and filmmaker (The Quiet in the Land and a documentary on the Amish which was broadcast on PBS).

History, faith, family and community are of utmost importance to Ruth. The reader feels the pulse of his striving for meaningful fulfillment and service wherever he finds himself, and his struggle for spiritual authenticity. The reader senses the tension of being in the world but not of the world, remaining true to Ruth’s Anabaptist faith and heritage. “It was a disturbing sensation to be diligently teaching American literature while feeling that the story of my own spiritual heritage was not reaching the next Mennonite generation,” the former professor of English at (what is now) Eastern University, St. Davids, Pa., writes of this internal conflict.

In 1973, TourMagination asked him to chaplain an Anabaptist Heritage Tour in Europe. Ruth writes this felt like “a second ordination” to spend the rest of his life promoting the Anabaptist Mennonite faith heritage through these tours.

The last picture in the book moves me deeply. On a heritage tour in Europe, a young boy, travelling with his aunt, asked to be baptized there in the land and faith of his ancestors. John Ruth is pictured baptizing the boy beside a small tributary of the Danube River which “had once run red with Anabaptist blood.

“Whatever streams we live by or travel on, our lives’ deepest currents are spiritual,” Ruth writes. “Mine, I hope, can be sensed flowing through this memoir with pictures, all the way from the first one taken by a mother, through a dozen by a father, to the closing one by a loving aunt.” His book has indeed been a “marriage of the head and heart.”

—Nancy Fehderau is a member of Kitchener (Ont.) MB Church.