Laura and Angela

Angela and I have known each other since we were 13. We met at Summer Magic day camp, where we both served as junior volunteers. I recall feeling very grown-up as Angela and I discussed future careers, family, faith, and – yes – boys! Over the ensuing years, we whiled away many hours, sipping strawberry tea and sharing from our hearts. I had the honour of helping Angela edit her thesis, and I’ve watched her become a successful counsellor with her own private practice.

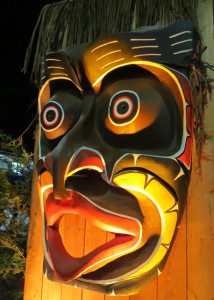

Angela is aboriginal. An Interior Salish from the Nlaka’pamux Nation near Merritt, B.C., Angela grew up visiting her dad, grandmother, and relatives on the reserve. She values aboriginal teachings, traditions, and commitment to family. She can recognize the unique drumbeat of her people when their songs are played.

Truth and reconciliation

When the opportunity arose for me to attend Vancouver’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), I immediately felt I needed to attend with Angela. I wanted to listen together as friends. I wanted her perspective as someone who had been personally affected by the residential school system in Canada.

When the opportunity arose for me to attend Vancouver’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), I immediately felt I needed to attend with Angela. I wanted to listen together as friends. I wanted her perspective as someone who had been personally affected by the residential school system in Canada.

The residential school system is a black mark in Canadian history. From the 1870s to 1996, some 150,000 First Nations, Metis, and Inuit children were taken from their families and communities and sent to government-funded, church-run schools. Many were forbidden to speak their language or practise their culture. Many were abused, malnourished, or neglected; hundreds committed suicide. Most experienced deep loneliness and sorrow. Canada estimates 70,000–80,000 former students are still alive today.

Witnesses

Angela and I were called to be witnesses to the stories of these residential school survivors, along with thousands of others who attended the event. We had a key role to play. In aboriginal cultures, witnesses are keepers of history when a significant event occurs. Organizers asked us to remember and repeat what we heard – to share the stories with our own communities when we returned home.

So Angela and I became witnesses during four days of vivid recollections, tears, gifts of reconciliation and, most importantly, hope.

My story

I was shocked and humbled by the stories I heard, and succumbed to tears on more than one occasion. The details were horrifying. Yet they were communicated with grace, strength, and dignity.

I met George in the display area, with his big smile, shaggy hair, and love of bluegrass gospel music. He told me about the time he and his brother went on their very first car ride. Elated, they waved to their parents from the rear window of the vehicle. In hindsight, George recalls tears slipping down his parents’ faces. He and his brother ended up at a residential school miles away, and wouldn’t return home for months.

I heard Phyllis’s account. At six years old, Phyllis’s grandmother took her to buy a special outfit for her first day of school. As part of her new ensemble, Phyllis chose an orange shirt and wore it with pride. But when she arrived at residential school, the teachers immediately took away her new clothes. The precious orange shirt was never seen again. “The colour orange has always reminded me of that and how my feelings didn’t matter, how no one cared, and how I felt I was worth nothing,” says Phyllis.

Then there was Doreen: “The priests and nuns made us kneel down and pray about our sins. We didn’t even know what sins were. So we just made them up.” Father, forgive your church!

As a witness to the TRC, I heard some terrible things. But as a witness of Jesus Christ “who comforts us in all our troubles, so that we can comfort those in any trouble with the comfort we ourselves receive from God” (2 Corinthians 1:4), my prayer is that we would draw on our own stories of suffering and faith, extending God’s comfort and hope to others who suffer. That’s what peacemaking and reconciliation look like to me.

Angela’s story

Angela was also brought to tears by what she heard. Unlike me, she wasn’t shocked by the details. She had heard them before. And she was already aware of the strength and resilience of her people.

Angela was also brought to tears by what she heard. Unlike me, she wasn’t shocked by the details. She had heard them before. And she was already aware of the strength and resilience of her people.

But she was surprised by the freedom she felt after being called an intergenerational survivor. It was a moment of validation for her. The pain her family had experienced – multiple traumatic losses – was part of a larger narrative, passed down through generations, interwoven within the history of her people and of Canada.

In those few days, Angela gained a new perspective on the challenges she continues to face as the granddaughter of a residential school survivor. It wasn’t by chance, or bad luck, or poor personal choices her family suffered.

The reality is that a country – and a church – believed the “savages” needed to be civilized, to have the Indian schooled out of them. In the words of Dr. Duncan Campbell Scott, head of the Department of Indian Affairs, 1913–1932, “I want to get rid of the Indian problem…. Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic.”

Toward a better future

Some do not understand the necessity of the TRC. Why don’t they get over it? They’re just looking for more handouts!

But wounds are still raw. It was only in 2007 that Canada’s Supreme Court, in a landmark settlement decision, recognized the horrible and lasting damage inflicted by the residential school system. It was only in 2008 that Prime Minister Harper offered an official apology on behalf of the government. And it’s only now that many survivors are sharing their stories – long-hidden hurts – with family members. The conversation has just begun.

So, what do Aboriginal Peoples want? Put simply, they long to be heard. Yes, I witnessed tirades about politics, land rights, and treaties. There were cries for justice. There were angry reminders that prejudice continues to this day.

But mostly, there were words of deep appreciation and genuine embrace for those who came to listen. There was an invitation to allow these stories to transport us all to a new place of understanding and respect; to recognize the courage and resilience of Aboriginal Peoples. In the words of one survivor: “My spirit was laid down, but now my spirit stands strong.”

My friend Angela is a survivor, too. She is part of a First Nations story. She is part of Canada’s story. And she is part of the solution that’s slowly bringing peace and reconciliation to this land.

And I pray I am too.

Mennonites offered an expression of reconciliation to their Aboriginal neighbours at the TRC in Vancouver, Sept. 18–21, 2013. Presenters included residential school survivor Isadore Charters (centre, in red) who gifted a copy of his 28-minute documentary Yummo Comes Home, which chronicles his story of healing and encounter with Jesus. Dave Heinrichs of Eagle Ridge Bible Fellowship, Don Klaassen of Sardis Community Church, and Garry Janzen of Mennonite Church Canada were also part of the delegation.