This article originally appeared in Sightings, an e-publication of the Martin Marty Center at the University of Chicago Divinity School.

The 2011 Canadian census data regarding religion was recently released by Statistics Canada, the federal agency that tells us Canadians, and interested others, what to make of the decennial censuses taken by the government.

The main plotline is the continued falling away of Canadians from the Christian religion. From the 1860s to the 1960s, Canada was one of the most observant Christian countries on earth. Through the 1940s, weekly church attendance was well above 60 percent (versus about 40 percent in the U.S.) and a broad cultural consensus existed around Christian values, institutions, customs, and religious language. As late as the 1970s, Canadian public school children recited the Lord’s Prayer at the start of every morning, and into the 1980s the Lord’s Day was observed by acts that bore its name – businesses were kept closed and entertainments curtailed to foster both worship for the faithful and rest for the weary.

The tight link between Canada and Christian piety has evaporated as Canadians have raced the Dutch for the fastest de-Christianization since the French Revolution. Yes, Quebec led the way with its Quiet Revolution – its rapid and radical secularization in the 1960s. The national story is simply an Even Quieter

The tight link between Canada and Christian piety has evaporated as Canadians have raced the Dutch for the fastest de-Christianization since the French Revolution. Yes, Quebec led the way with its Quiet Revolution – its rapid and radical secularization in the 1960s. The national story is simply an Even Quieter

Revolution of slow, but sure, abandonment of Christian identity by older people and an increasing number of younger people who have never known the inside of a church and are in no hurry to see it.

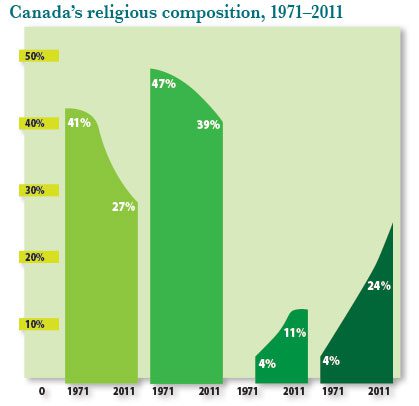

According to Canada’s 2011 National Household Survey, the religion with the most adherents remains, unsurprisingly, Christianity. Of roughly 33 million Canadians, almost exactly two-thirds (67.3 percent) were affiliated with a Christian denomination. In 1991, by comparison, that number was 83 percent. Roman Catholics continue to dominate nationally (not just in Quebec), with fully 39 percent of the population.

The two major Protestant denominations, United (produced by the merger of four denominations in 1925) and Anglican, have been in steady decline since the 1960s and, between them, claim a mere 11 percent of the population. That leaves about 17 percent of Canadians distributed over various believer’s churches (Baptists, Pentecostals, and the like), Holiness traditions, Lutheranism, Orthodoxy, and a few others.

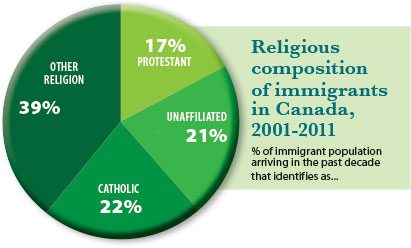

Has Canada’s liberal policy of welcoming immigrants from all over the world significantly altered the religious landscape? Only a little. Between them, “proper-noun” religions beyond Christianity (including Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, and Buddhism) accounted for 8 percent of the population, up from about 6 percent ten years ago. And almost 50 percent of recent immigrants claimed, in fact, Christian identity.

So Canada has not yet been substantially altered by an influx of non-Christian religions – even as Canada’s largest cities, Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver, which are home to the vast majority of devotees of those religions, feel the concentrated influence of such groups in some of their suburbs.

Sources: 1971–2001 Canada census; 2011 National Household Survey *Data for the “other religion” category in 1971 are not shown because the figure isn’t comparable with the figures for 1981–2011. PEW RESEARCH CENTRE graph

The key change, however, is the complement to the decline in Christianity. About 8 million Canadians, or 25 percent of the population, espoused no religious affiliation. This was up from 17 percent a decade earlier, and about 13 percent in 1991.

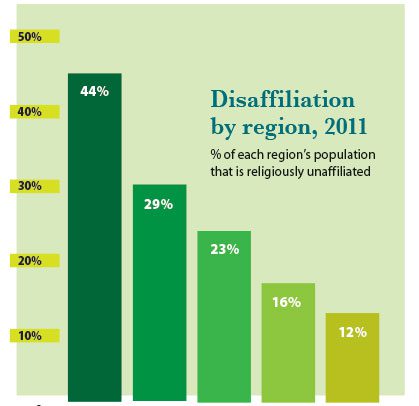

The share of people with no religious affiliation was highest in Ontario and British Columbia. More than a million people in the Toronto area, or about 20 percent of its population, had no religious affiliation. In the much smaller metropolitan area of Vancouver, over 40 percent reported no affiliation.

In sum, Canada as a whole is not yet so much a multi-religious country yet as it is a Christian/ex-Christian/sort-of-Christian country, with an ongoing shrinkage of Christian affiliation. (Other polls show that only Roman Catholics and evangelicals are holding their own – mostly by retaining youths in much higher numbers than other Christian traditions.)

Quebec continues a European pattern of very low church attendance coupled with a relatively high nominal affiliation with the Roman Catholic Church, while the largest and most culturally influential centres of Anglophone Canada report the highest levels of both religious “alternatives” and religious “nones.”

Thus, despite Canada’s proximity to the United States, its cultural patterns show more affinity to its French and British heritages.

Unless, that is, the United States is simply following in Canada’s train. Despite amplified voices of various American political and religious leaders that prompt Americans and Canadians alike to think of the United States as still a robustly Christian country, disaffiliation (in dropping church attendance) shows up increasingly in increasingly candid polls of nominal affiliation.

But that’s a story for an American, such as Martin Marty, to tell Sightings readers, not me.

This article originally appeared in Sightings, an e-publication of the Martin Marty Center at the University of Chicago Divinity School (divinity.uchicago.edu).

—John G. Stackhouse, Jr., holds his M.A. from Wheaton College where he studied under Mark Noll, and earned his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago Divinity School where he studied under Martin Marty. He is the Sangwoo Youtong Chee Professor of Theology and Culture at Regent College in Vancouver, and the author of Canadian Evangelicalism in the Twentieth Century: An Introduction to Its Character (University of Toronto Press, 1993).

—John G. Stackhouse, Jr., holds his M.A. from Wheaton College where he studied under Mark Noll, and earned his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago Divinity School where he studied under Martin Marty. He is the Sangwoo Youtong Chee Professor of Theology and Culture at Regent College in Vancouver, and the author of Canadian Evangelicalism in the Twentieth Century: An Introduction to Its Character (University of Toronto Press, 1993).