Surveying the landscape of Mennonite Brethren and Aboriginal ministry

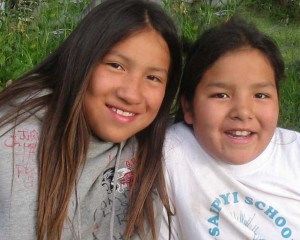

Campers and counsellors play a game at Gladstone Gathering Grounds, a NAIM camp in southern Alberta.

From their beginnings, the Mennonite Brethren held mission as a high priority. Within 30 years of establishing the denomination, they were sending missionaries to evangelize Indians on the Asian subcontinent. In that same period, Mennonites began migrating to Canada, where they met a group of people, also, at that time, called Indians.

But while evangelism in India led to a vibrant church (now one of the largest national MB conferences in the world, under indigenous leadership for 50 years), MB interaction with “Indians” in Canada was minimal. Today not a single Canadian MB church can be identified as a “First Nations” or “Aboriginal” church, nor are there many in MB congregations who self-identify as such.

In June 2008, Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper’s official apology to the First Nations people of Canada for their treatment in residential schools, once more brought Aboriginal Peoples into the consciousness of Canadian society at large. Social problems and poverty in many Aboriginal communities evidence the “lasting and damaging impact on Aboriginal culture, heritage, and language” cited by Harper.

Racism

All Canadians are affected by the poverty of First Nations people, says national chief Phil Fontaine: “This is not just a burden on our people. It’s a burden on the entire country.” Craig Benjamin, spokesperson for Amnesty International, says, furthermore, that racism is endemic both to the government and to Canadians who have not cried out for better. The Mennonite Brethren are not exempt.

All Canadians are affected by the poverty of First Nations people, says national chief Phil Fontaine: “This is not just a burden on our people. It’s a burden on the entire country.” Craig Benjamin, spokesperson for Amnesty International, says, furthermore, that racism is endemic both to the government and to Canadians who have not cried out for better. The Mennonite Brethren are not exempt.

Brian Wiens, a pastor at Parliament Community Church in Regina, confesses this responsibility. “Even as someone who grew up in northern Saskatchewan and went to school with many First Nations neighbours, I have been more influenced by racism and a sense of superiority than I’d like to admit,” he says.

Parliament Community Church has a long-standing partnership with Healing Hearts, a ministry to Regina’s North Central neighbourhood. North Central grabbed Maclean’s magazine headlines in 2007 as “worst neighbourhood in Canada.” According to census figures, 42 percent of the residents are of First Nations ancestry, a demographic that bucks the provincial trend with rising birth rates instead of a greying population. Crime, poverty, and unemployment figures for the neighbourhood are disturbingly high.

“There is, to some degree, resentment toward the First Nations community – that they’re getting a free ride from our tax dollars,” suggests Wiens. “It’s hard to swallow for hardworking Mennonites.”

But in a situation where those involved say building relationships is the best way to minister, underlying resentment can sabotage our ability to care for and love people, and to treat them as equals. The government’s approach, and most citizens’ with it, has swung from the forced assimilation of the residential school years to entrenchment of Aboriginal rights from the 1980s onward, says Jack Hooge, a former missionary with North America Indigenous Ministries (NAIM). “Both policies have served to alienate Native people from entering into full partnership in our country,” he says.

Building relationships

Out of the seeds planted in the past and today, Aboriginal believers have sprung to faith. Though “there is still much need for ‘rescue’ work, Native people are capable of running their own affairs, and missionaries need to be willing to step back and allow it to happen,” says Hooge. Effective work that offers healing and growth to both parties requires “egalitarian relationships with our Native brothers and sisters,” he says.

Across the isolated communities of northern Manitoba, there are Aboriginal Christians, “men and women of remarkable faith and devotion,” says Bob Hay, who has spent a lifetime in the region, working both in the mining industry and in education. Over the years, Hay has opened his home to hundreds of northern youth, witnessing first-hand the struggles and triumphs of the Aboriginal community in the region. “It’s not easy to be a Christian in the North,” he says.

The process of growing faith toward a degree of self-determination is a long process, says Nick Helliwell, an Aboriginal minister with Healing Hearts. The First Nations community has often fallen prey to a mindset of dependency, he says, and the church needs to “model the Christian ideal of responsibility as well as forgiveness in the community.” The devastating effect of the residential schools has left generations without a sense of identity and role in society.

“As a Christian, I am aware that only covered by the blood of Jesus Christ am I fully restored to my heavenly identity as a child of God,” says Helliwell of his journey.

Dennis Reimer knows the work of relationship-building as mission can take a long time. For more than 10 years, he has participated in a Bible study on a reserve in southern Manitoba, where attendance fluctuates from two or three people to 20 from one week to the next. Nevertheless, he says, his weekly visit to the reserve is “probably the most spiritually meaningful two hours in my week.”

Reimer has a heart to see Aboriginal people take over the study and provide spiritual leadership on the reserve. “We’re a pilot light keeping the fire going,” he says of his and fellow church members’ involvement with their neighbouring community. “When the Lord has prepared enough fuel, the thing will burst into flame and we won’t be needed anymore.”

Reimer has a heart to see Aboriginal people take over the study and provide spiritual leadership on the reserve. “We’re a pilot light keeping the fire going,” he says of his and fellow church members’ involvement with their neighbouring community. “When the Lord has prepared enough fuel, the thing will burst into flame and we won’t be needed anymore.”

“We’ll know we’re equals when we can have a Native minister of a primarily white congregation,” Reimer adds.

North Fraser Community Church in Lake Errock, B.C., is a place where people of Dutch, First Nations, German, French, Korean, and Spanish descent worship together. Pastor Alec Niemi strives to be “inclusive and integrative, accepting and accommodating” to the many ethnicities represented in his community, so they can hear that “it’s the gospel that changes the hearts of all people.”

The sense of equality Niemi cultivates is what draws George Brown, a First Nations member, to drive 40 minutes to attend church on Sundays. The church “walks beside [me] rather than in front of [me],” says Brown.

Culture gap

Yet there is a gap to be bridged between the assumptions and cultural understandings of the largely white, middle-class members of European descent, who make up a large percentage of MB members in Canada, and Aboriginal Peoples.

Mennonite Central Committee’s Aboriginal Neighbours program uses a combination of dialogue, advocacy, and community-building support to provide bridges and create space for relationships between Mennonites and First Nations people to “partner in God’s work of reconciliation” across Canada.

“The Aboriginal church will never look like the mainstream churches around them,” says Ellen Hooge of NAIM, who develops Sunday school curricula for Native children. The greatest need of the Aboriginal fellowships “popping up all over North America,” she says, is for culturally relevant materials to “facilitate the Aboriginal church in sharing the gospel with their people – and the world.”

Mennonite Church Canada has developed a Sunday school curriculum for use by Aboriginals and non-Aboriginals alike. Called Reaching up to God our Creator, the curriculum “explores the wisdom of Jesus Christ that is present in Aboriginal sacred teachings.” The producers say it allows both groups to “be blessed by the cultural and racial distinctives as well as the under-girding wisdom of Christ.”

Resources and training are needed to support people in the community already doing the work, says Hay. Another project, which makes Christian teaching more accessible to some Aboriginals, is the Canadian Bible Society’s Ojibwa Bible, relaunched in 2008, containing the New Testament and 50 percent of the Old Testament in “di-script,” Roman script set alongside Ojibwa syllabics.

Fish out of water

Building relationships, trust, and a sense of hope are key to all these ministries, formal or grassroots. Student Elya Penner came away from Bethany College’s annual week-long immersion on a rural reserve saying, “there is much pain, much healing that still needs to take place, but we witnessed much beauty.” Over six years of cultural awareness trips, the school has earned the trust of community leaders through the students’ willingness to learn about Cree culture, and get to know the people they meet.

“Instead of bringing or doing something for [the people on the reserve], the most we had to offer was our time,” says Lance Brown, another Bethany student. “It does no good to try and change their ways or tell them about Jesus if you first haven’t proved you’re willing to become their friend.”

“Having a listening attitude is so important because it changes my perspective and whole attitude going in, to care, listen, and learn,” says Wiens. As he interacts with Aboriginal people, he often learns as much about himself and his own need to grow as he offers help.

“If people understood how great the blessing is, you’d have people clamouring to have more diversity in the fellowship,” says Reimer. But the trick is, “you have to be willing to be the fish out of water.”

—Karla Braun is MB Herald assistant editor.

___________________________________________________

A brief history

Mennonite Brethren of North America established a mission among the Comanche Indians of Oklahoma in 1896. It was not until 1907 that the first baptism took place, but the Post Oak Mission became, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society, “arguably the most successful” in western Oklahoma. The Post Oak MB Church still exists.

In Canada, MB mission to First Nations communities evolved in fits, starts, and stops. These are some recorded initiatives:

- 19 Mennonite Brethren conscientious objectors taught school on Native reserves in United Church posts in northern Manitoba vacated by World War II’s call for conscripts.

- Initiatives in interior B.C. after World War II, also often tied with teaching posts, resulted in some mission churches which later fizzled due to competing interests of Aboriginal, Japanese, and Caucasian members, or transferred their allegiance to other denominations.

- In the early 1970s, the B.C. conference withdrew from direct involvement in Aboriginal ministry in Port Edward, but resolved to support the work of North American Indigenous Mission (NAIM).

- Saskatoon Native Mennonite Brethren Church appears in conference yearbooks for 1981 and 1982 with 10 members, then disappears from 1983 on.

- In 1988, Mission and Church Extension of Manitoba pushed a recommendation to plant a Native church in Winnipeg, but the church planter and the conference parted ways; by 1994 a “heart connection” was cited between the parties without a formal relationship.

- The Alberta conference decided that the work being done in Hobbema “does not fit into [its] Policies and Procedure” and was pleased to pass the work on to Northern Canada Evangelical Mission. The conference concluded officially funding NCEM in 1994.

—KB, with files from A History of the Mennonite Brethren Church, No Longer at Arms Length, “Mennonite COs and the United Church in Northern Aboriginal Communities” in Journal of Mennonite Studies, MB Herald, Saskatchewan MB Conference Year Book, www.gameo.org.