Winnipeg

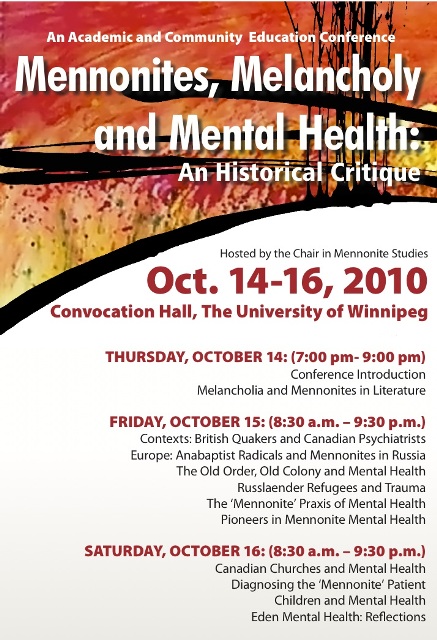

Mennonites are not unique in their experience of mental illness, but they have, at times, stood out from society in their compassionate response to it. That was one of the themes that emerged at this year’s iteration of the annual Divergent Voices of Mennonites in Canada conference, “Mennonites, Melancholy and Mental Health: An Historical Critique,” hosted by the Chair in Mennonite Studies at the University of Winnipeg, Man., Oct. 14–16.

Mennonites are not unique in their experience of mental illness, but they have, at times, stood out from society in their compassionate response to it. That was one of the themes that emerged at this year’s iteration of the annual Divergent Voices of Mennonites in Canada conference, “Mennonites, Melancholy and Mental Health: An Historical Critique,” hosted by the Chair in Mennonite Studies at the University of Winnipeg, Man., Oct. 14–16.

Twenty-five scholars from across Canada and the U.S. presented papers on Mennonite interaction with mental illness, institutions for care and treatment, mental illness in particular demographics (e.g. children, Old Order groups), and creative/cathartic writing, or gave a personal reflection. The nine thematic groupings of presentations were complemented by two panels of practitioners, including past and present CEOs, and the former director of spiritual care at Eden Health Care Services in Manitoba, and a psychiatrist and nurse working in the public square.

While Mennonites have, as a people, experienced trauma, e.g., in post-revolution Russia, they should recognize their trauma is not unique among immigrants, Elizabeth Krahn noted at the end of her paper, “Lifespan and Intergenerational Effects of Soviet Oppression.” Psychotherapist Annie Wenger-Nabigon urged Mennonites to recognize they have been complicit in the historical and continuing traumatizing of First Nations people in North America. “The fact that we live on stolen land is something we must always remember.”

Faith-motivated care

Christian faith motivates Mennonite care that has at times differed from the treatment offered by secular institutions. Early Anabaptist leader Pilgram Marpeck called the church a “hospital,” offering healing to those with mental illness through forgiveness and joy, unlike wider society at the time which persecuted “witches” and the “possessed,” said William Klassen in “Duke Ferdinand vs Pilgram Marpeck: Lunatics or Preachers of Care.” More recently, Mennonite Canadian conscientious objectors and Americans in Civilian Public Service during World War II worked in mental hospitals, where they decried inhumane treatment of patients, said Conrad Stoesz, from his paper “‘Are you prepared to work in a mental hospital?’: Canadian Conscientious Objectors’ Service during the Second World War.”

But Mennonites more recently have only kept pace with wider society’s move toward more holistic care, conceded Irma Janzen, former director for Mennonite Central Committee’s mental health and disabilities program. Articles in the MB Herald of the 1960s and 70s spoke about mental illness mainly as something to be persevered through with prayer and stoicism, Ellen Paulley observed in “Mental Illness in the MB Herald, Canadian Mennonite, and Mennonite Mirror.” Krahn said traumatized women were unable to discuss their problems with either ministers or other women for fear of dismissal or vicious gossip.

The panels of practitioners spoke of learning from the best aspects of both secular scholarship and Christian spiritual teaching to practice a more compassionate and balanced approach to mental illness. While Mennonite institutions like Eden have provided successful examples to society of the holistic treatment of mental illness, and have sought to dissolve the stigma of mental illness, “the church itself needs to learn how to integrate what it means to have faith and work with those in need,” said current Eden CEO James Friesen.

—Karla Braun